History of the Museum. XIX Century

«…to have the Cabinet composed of Russian and foreign minerals and fossil bodies, and henceforth thereof to be composed, available at the Mining School in a constant manner …»

from memoirs of contemporaries

In 1804 a new charter, under which the Mining School was reorganised into the Mining Cadet Corps, was approved, giving the university a higher status.

Small buildings acquired in the 18th century could no longer suffice the growing institution. So in 1806, Emperor Alexander I of Russia signed a special decree to establish a commission for rebuilding the Mining Cadet Corps, headed by Andrey Voronikhin. The 18th-century detached buildings were merged into one, with the construction of a new architectural complex completed by 1811.

The solemn and majestic building designed by Voronikhin became a finishing touch to the classic ensemble built on the banks of the Neva River.

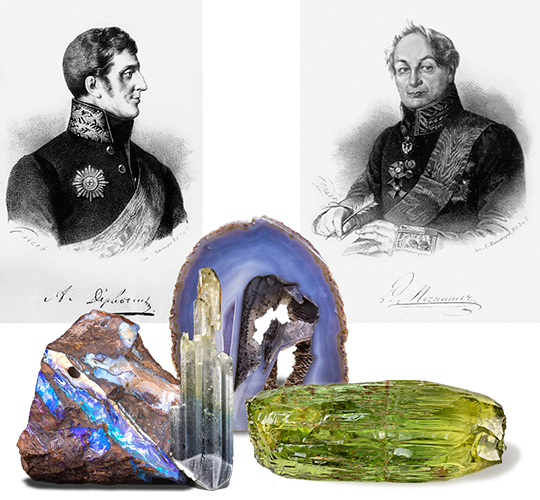

Upon completing the construction works, Andrey Deryabin, director of the Mining Cadet Corps, arranged an expedition to collect mineralogical and geological material in Siberia and the Ural. Its purpose was to replenish the museum's collections, and it yielded over 50,000 items — various ores, rocks, and minerals among them. Some of them became part of the museum's core collection; others formed the base of the natural-resource fund.

In 1812, a new curator was appointed to the museum – Dmitry Sokolov – who started systematising the existing collections according to the latest scientific knowledge.

Unexpectedly, all the work on enlarging and reorganising the museum's collections had to be stopped. As the Patriotic War of 1812 was declared, it was decided to evacuate the unique collectables to preserve them. Barques arrived right at the quay in front of the Mining Corps; loaded with the museum's valuables, they left to the Svir River. All the items were retrieved undamaged in 1813.

Developments in science and changes in the educational system forced the museum to reorganise its entire old collection and start arranging the new ones in systematic order. The transformation project envisaged expanding the museum's premises, adding new and systematising existing items.

The Decree of Emperor Alexander I of April 10 (March 30), 1816, on transferring the collection of minerals and rare fossils from the Hermitage to the Mining Cadet Corps for permanent display was a significant step in replenishing its natural-scientific troves. Most of the collection were items from the mineral cabinet of Empress Catherine II.

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN OF THE MUSEUM

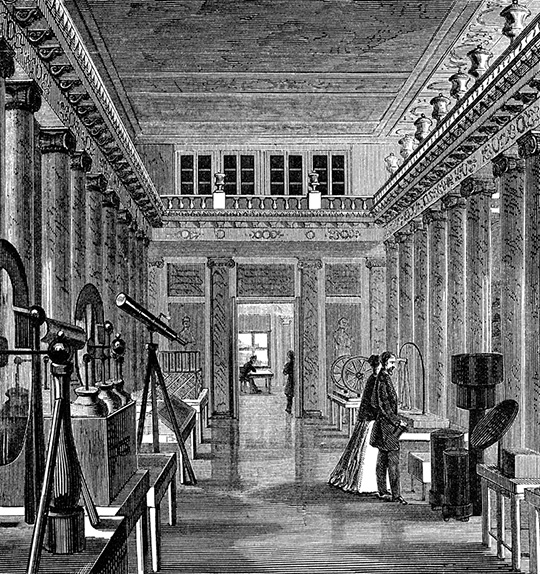

In 1821-26, during the extensive reconstruction of the Mining Institute supervised by the architect Alexander Postnikov, the interiors of the majority of the museum's halls were redecorated with Empire ornament. The Column Hall owes its splendour especially to a plafond by Giovanni Battista Scotti, the greatest muralist of the early 19th century. The plafond features an allegorical panel of three elements: 1. In the form of virtue, Russia approaches the temple built to glorify the sons of the fatherland. Therein those express their gratitude for the favours and privileges granted by Emperor Alexander I to the Mining Cadet Corps. 2. Catherine II, who established the Mining School, instils obedience in old boys to the ruler and encourages them to work and acquire the knowledge of sciences taught at the institution. 3. In the centre, Peter the Great, founder of the mining industry in Russia, observes the progress and development of the latter with satisfaction.

MINERAL CABINET OF THE MINING CORPS

In 1821, the abundance of the museum's unique collection was described by Pavel Svinyin in Otechestvennye Zapiski. He wrote:

«<…>the entire cabinet was still housed in the Column Hall that had been by then redecorated. On top of all the cases were placed the busts of philosophers and famous scientists of antiquity. The display cases themselves were inscribed in golden letters with the names of the minerals put inside. The rarest, unusually shaped, and large-size specimens were positioned on the windows under tailor-made glass covers. The objects of enormous size were installed onto special pedestals between the columns. The physical instruments were shown off in the centre of the hall. In the 1820s, the mineral cabinet of the Mining Cadet Corps had on display: a massive chunk of Ural malachite, a copper nugget weighing over 100 kg – the largest in Russia at that time, large druses of native sulphur, a gigantic quartz crystal of 500 kilograms in weight, native silver and gold, samples of fluorite, pyrite, etc.».

The renovated museum space was equipped with the new furniture – showcases and cabinets – performed in one style to match the architectural design of the halls. Several display cabinets, created by the court furniture-maker Christian Meÿer, belonged to Catherine II herself and served to store and exhibit the Empress' private mineral collection. Along with the collectables, they were later transferred to the museum of the Mining Cadet Corps.

The expositions of the Russian topographical collection (now the Malachite Hall) were completed in 1828 with the transfer of the largest-sized exhibits from the old mineral cabinet (the Column Hall).

The evidence of contemporaries suggests that the museum of the Mining Cadet Corps was one of the largest in St. Petersburg in the first quarter of the 19th century. Since 1825, following the order of Emperor Nicholas I, therein were reposited all nuggets of precious metals from the Saint Petersburg Mint. They were put on display in special cast-iron safe boxes. In addition, a sizeable section was allocated to the models of mining equipment used in the early 19th century.

Many well-known and reputable people holding public offices offered donations to expand the museum's collections. Among them were Count Karl Nesselrode, Vice-Chancellor, Count Lev Perovksy, Minister of Domains, Pavel Svinyin, a Russian writer and editor, and others. The museum was under the constant patronage of the imperial family. In 1829, following the eruption of volcanoes in Italy, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna ordered an original collection of eruption products to be assembled and reposited in the museum. Large subsidies from the treasury were regularly granted for the purchase of private collections. Additionally, new exhibits were sent in by the direct orders of the emperors, including the largest-ever copper nugget of 842 kg and a druse of the purest rock crystal from Japan.

From the 1830s to 1866, most of the attention was paid to enriching palaeontological and geological collections. Previously, they remained in the background of the mineralogical and model collections. The situation started gradually changing as Konstantin Chevkin was appointed Chief of Staff of the Institute of the Corps of Mining Engineers in 1834. From 1840 on, the Russian Geological Assembly was headed by Gregor von Helmersen. Vasily Nefedyev was in charge of the mineralogy section. In 1871, he published the first printed catalogue of the museum's mineralogical collection.

The basic structure of the museum, the principles of arranging exhibition material, and the methods of delivering lectures and practical classes took shape in the 19th century. At the same time, the museum acquired quite a few collectables and a fair amount of teaching material. By the mid-19th century, the geological collections had grown significantly, and the museum's administration once again faced the need to expand. Consequently, in 1866 the boarding house for students was closed. Thereupon the rooms that had served before as dortours were given to the museum. After the reconstruction, the Russian Geological Assembly was housed therein, whilst the museum has since occupied most of the first floor of the main building.

In the late 19th century, the museum replenished its funds with the extensive collections of minerals by Johann Walcker and Alexander Grammatchikov, rocks from Sweden and Finland by Nils Nordenskiöld. In addition, several thousands of minerals were received under the will of Nicholas, Duke of Leuchtenberg. Some unique palaeontological monographic collections were passed on to the museum, including those of most renowned geologists and palaeontologists of Russia and Europe: Joseph Lahusen, Yevgeny Barbot de Marni, Otto Wilhelm Hermann von Abich, Johann Friedrich von Brandt, others.

Despite significant material costs, the Mining Institute's administration commissioned technical models to Europe's best mechanics and model-makers: F.A. Klopfer, K. Schumann, H. Schroeder in Germany; A. Clair, E. Bourdon, and E. Philippe in France. In the 19th century, solid connections were made with the Halsbrücke machine workshop near Freiberg, Germany. Models were also manufactured within the institute, at Saint Petersburg Mint, and at Russian mining factories. In the last few decades of the century, a considerable role in expanding the museum's collection of models was played by graduates of the Mining Institute. They donated models of their own engineering developments. The museum was regularly provided with items exhibited at all-Russian and global trade fairs. Among them are showpieces from the fair of 1839 in St. Petersburg, the polytechnical exhibition of 1872 in Moscow, the world's fair of 1873 in Vienna, the exposition of 1876 in Philadelphia, the industrial fair of 1896 in Nizhny Novgorod, and the world's fair of 1900 in Paris.

The model section was enriched with numerous exhibits: a model of the regenerative hot blast stove by Edward Cowper, a model of shaft houses, coal-lifting devices, and coke ovens by Coppée, and others.